Idiopathic—It’s Gonna Be Weird

I have a special place for broken-down clowns in my broken-down heart. A few years ago, I concluded that the dude I was hanging out with for months was never going to actually ask me out on a date and I would need to take matters into my own hands. I invited him to be my escort to the Boulder Fringe Festival. I picked him up wearing lipstick, a fancy sundress embroidered with chevrons, and beaded sandals. He wore cargo shorts, flip-flops, and a t-shirt he got for free at a software conference. I felt super special. We spent almost an hour watching a silent clown make his musical way through the world wearing a pink Lycra bodysuit, a cowbell, and an enormous diaper. It was tremendously weird, and so was the clown. Now, almost three years later—with my heart still festering from recently breaking up with a guy who has no fashion sense, but who will sit with me, unflinching, through 45 minutes of silent clowning—another upcoming show is featuring the same performer in a new format. Of course I had to see it.

I have a special place for broken-down clowns in my broken-down heart. A few years ago, I concluded that the dude I was hanging out with for months was never going to actually ask me out on a date and I would need to take matters into my own hands. I invited him to be my escort to the Boulder Fringe Festival. I picked him up wearing lipstick, a fancy sundress embroidered with chevrons, and beaded sandals. He wore cargo shorts, flip-flops, and a t-shirt he got for free at a software conference. I felt super special. We spent almost an hour watching a silent clown make his musical way through the world wearing a pink Lycra bodysuit, a cowbell, and an enormous diaper. It was tremendously weird, and so was the clown. Now, almost three years later—with my heart still festering from recently breaking up with a guy who has no fashion sense, but who will sit with me, unflinching, through 45 minutes of silent clowning—another upcoming show is featuring the same performer in a new format. Of course I had to see it.

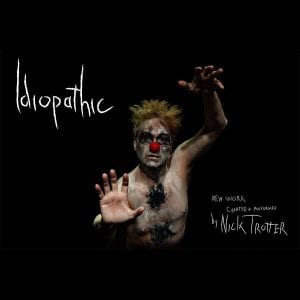

I don’t mean to say that I didn’t enjoy the previous clown performance, because I genuinely did. It was super weird, but so am I; I was just distracted by the overwhelming sexual desire inflamed in me by Linux Plumbers t-shirts. The type of clowning enacted that day was not the Ronald-McDonald kind or the frizzy-wig-birthday-party kind, neither of which I can muster up much appreciation for. It was a modern take on an ancient form of theatrical arts called Commedia dell’arte, wherein basic characters are brought to life in ever-changing, improvisational ways and used to provoke both comedy and commentary, superficial laughs and deep insight. It’s physical humor at its most intelligent, slapstick in a champagne flute. The creator and performer of that long-ago show, an auteur and mask-maker named Nick Trotter, has dropped the pink Lycra but retained the enormous diaper to use his training as a Commedia artist to explore some new parts of the human psyche on stage at the People’s Building on February 28-March 2.

The sad or downtrodden clown is a longstanding character in theatre and it’s reinvented here for a new look at idiopathy. The new show is called Idiopathic, meaning “one’s own suffering.” It’s a term often used in medicine to describe a problem not originating in any pathogen or physical disease state, but brought about by the patient’s own psyche. Trotter uses it here to dive into the spooky and frankly sometimes-scary parts of humanity and himself from whence spring addiction, insomnia, and a host of other warped behaviors so commonplace to so many of us. Where do these cycles begin, and how do we (or how can we) stop them?

Addiction can manifest differently for each of us. Does the definition of “alcoholic” depend on how much you drink or why you drink? Is a heartbreak that won’t ever heal conceptually different than the opioid-dependent person who has completed withdrawal (“breakup”), but still longs for that old, sweet rush? Some of same brain circuitry is triggered in early-stage romance and drug use; it’s the endings that differ in their joy or tragedy. Insomnia, too, is a poisonous cocktail of anxiety, depression, and circadian rhythm disruption. The cycles begin the same way, but are stopped differently. Now, think about the content of this paragraph, but imagine it in humanoid form, dressed in leached-out whiteface and a big, bundled loincloth. That’s a pretty good starting point for considering the staging of Idiopathic.

Trotter dresses up (or, more accurately, hardly dresses at all) in his rumpled butt-bundle and occupies the stage to embody and explore frustrations, obsessions, and releases, but he doesn’t do it alone. He’s accompanied by a great deal of full-body makeup and Saladin Thomas, drummer for the Denver-based band To Be Astronauts and a well-respected performer in the Denver improv scene. The makeup is mute; Thomas’ drums definitely are not. The score is partly composed and partly improvised. Thomas and Trotter interplay with motion and music as they lead and follow each other around the piece, listening and reacting to the other’s offerings. It’s a physical and psychological ballet, with makeup and inventive percussion. I found it fascinating, disturbing, and slightly hypnotic. Musical scores add hugely to the impact of performances, of course, and the single percussionist of this piece seems particularly enhancing to the physical movements of the actor. Just one body; just one internal/external beating series of sound. Which comes first: movement or sound, distress or disorder? Yes.

Trotter dresses up (or, more accurately, hardly dresses at all) in his rumpled butt-bundle and occupies the stage to embody and explore frustrations, obsessions, and releases, but he doesn’t do it alone. He’s accompanied by a great deal of full-body makeup and Saladin Thomas, drummer for the Denver-based band To Be Astronauts and a well-respected performer in the Denver improv scene. The makeup is mute; Thomas’ drums definitely are not. The score is partly composed and partly improvised. Thomas and Trotter interplay with motion and music as they lead and follow each other around the piece, listening and reacting to the other’s offerings. It’s a physical and psychological ballet, with makeup and inventive percussion. I found it fascinating, disturbing, and slightly hypnotic. Musical scores add hugely to the impact of performances, of course, and the single percussionist of this piece seems particularly enhancing to the physical movements of the actor. Just one body; just one internal/external beating series of sound. Which comes first: movement or sound, distress or disorder? Yes.

I have to say that this piece, like the other of Trotter’s creations that I witnessed, is a little weird. Maybe even a lot weird. (I will state that the doldrums of late February/early March are a particularly good time to explore some weirdness in your life.) I’m generally one to like a palpable narrative structure in my performing arts and this one didn’t hand that to me with a bow on top. I recognize that it wasn’t supposed to do that, but I still felt like I wanted it. I think this piece wanted me to consider the creative process and how that influences us as individuals living our lives and struggling against the enormity of our adverse influences. Or maybe not. Maybe it’s just a clown and a drummer duking it out on a late-winter night while democracy falls and the oceans rise. Either way, it’s not quite a soothing experience.

This column doesn’t have a really tidy wrap-up and that’s appropriate both to the performance piece I’m reviewing and the issues it explores. We fall into cycles of destruction and, we hope, we crawl out into redemption. Broken hearts heal, most of the time. Art is a way we process and cope with all these afflictions and resurrections. I will say two things in closing. First, this new show is well worth the ticket price, if you’re up for something avante-garde during the first weekend of March. Second, that hideous diaper is still an improvement over a Linux t-shirt.